Welcome

Whether you are preparing to fly to the stars …

Section titled “Whether you are preparing to fly to the stars …”Or just get trying to get out of bed in the morning, you probably have many basic questions about life:

- Where did the universe came from?

- Is everything run by supernatural forces?

- How did we as human beings get here?

- How should I spend my time?

- What happens to us after we die?

- Is there really any way to answer these questions, or to be confident about anything?

If you are willing to pursue controversial questions no matter where they lead, and if you insist on evidence before accepting any answer, then you already share a basic kinship with Epicurus. That’s the type of person Epicurus was, that’s the attitude he built into his philosophy, and that’s the type of person who will feel at home at here at EpicurusToday and at EpicureanFriends.com, our online community.

Where Do I Start?

Section titled “Where Do I Start?”Epicurean philosophy is not difficult, but gaining a clear understanding of it requires time and effort. Epicurus cannot be understood by reading a couple of paragraphs about pleasure or absence of pain at Wikipedia. Epicurean philosophy is deeply controversial and revolutionary in its implications.

Here at the beginning is a simple list of key top-level conclusions that are emphasized at EpicurusToday and EpicureanFriends.com. As you may notice, this is not the full list contained in the ancient list of Epicurus’ Principal Doctrines, or in his “Vatican” list of sayings. This shorter list has been selected to emphasize the doctrines of Epicurus that are most starkly different from conventional modern ideas. Even this shorter list cannot be understand at first glance, for many people this will be enough to indicate whether they will find themselves at home with Epicurus:

Epicurus’ Paradigm-Changing Views of Virtue, Pleasure, Death, and Gods

Section titled “Epicurus’ Paradigm-Changing Views of Virtue, Pleasure, Death, and Gods”It cannot be emphasized enough that Epicurus uses important philosophical terms in very non-standard ways. Epicurus’ innovative views of “pleasure” and “virtue” and “gods” were controversial even in his own time, and we must understand why he departed from common usage if we wish to understand his philosophy as a whole.

Epicurus held that certain things in ordinary life clear and need no elaborate definitions. It is sufficient, for example, to point to fire to understand that it is hot; to snow to understand that it is white, and to honey to understand that it is sweet.

More complicated ideas, however, like “Virtue,” “Death,” and “Gods,” are not directly visible or touchable, and they require further explanation. Even “Pleasure,” which is not an abstraction when referring to ice cream, requires explanation when the term is used to describe a goal of life.

The difference between those things that require no explanation and abstractions that do require explanation was expressed by Torquatus an Epicurean spokesman found in the works of Cicero, as follows:

Epicurus held that many ideas about the nature of the universe commonly held in his day were totally wrong. Even more, however, he held that similar errors existed in common attitudes about the best way for humans to live.

Just as Epicurus rejected “earth, air, wind, and fire” as the elements of all things, he rejected conventional views of death, and the nature of gods, and the best way to live. Here are some of Epicurus’ most controversial viewpoints:

Virtue

Section titled “Virtue”Given that the universe is composed of particles moving through void, Epicurus saw that there can be no such thing as absolute and universal ethical laws, written for all time and places and people. What would be the source or authority of such law if there is no center to the universe, no single perspective that can be deemed eternally correct?

In such a universe there is no possibility of a supernatural god establishing absolute rules of conduct. As a result, Virtue in Epicurean terms is necessarily contextual, and seen as a set of tools to be employed in life which will vary in nature and use along with individual needs, desires, and other circumstances.

Virtue cannot therefore be an end in itself, or its own reward. Virtue in Epicurean terms is an important tool, but it is a tool invented by human beings for the sake of something else. In a totally natural universe in which there are no supernatural gods and no absolute virtue, what can that “something else” be?

Pleasure

Section titled “Pleasure”The “something else” for which virtue is but a tool is in Epicurean terms none other than the feeling of “Pleasure.” Pleasure, however, has a sweeping but very specific meaning in Epicurean terminology. Epicurus held that there are only two categories of feelings, and all evaluations of what is desirable and what is undesirable in life are ultimately within one of the two. These two very broad categories of feelings are “Pleasure” and “Pain.” The second of these, with which our current definitions are most consistent, is “pain.” Pain is any mental or physical feeling which we find to be undesirable in itself - in a word - painful. When Epicurus speaks of pain, we have no problem applying our standard perspectives and understanding what he means.

Pleasure, on the other hand, is in Epicurean terms a much more sweeping concept than which most of us appreciate. If some feelings are clearly painful and undesirable in themselves, and if there are only two categories of feelings, then what type of feelings are left to fall under the category of Pleasure? Simply put, all feelings of life, whether mental, physical, emotional, or whatever qualifying words you wish to employ, which are not in themselves painful are Pleasurable.

This view of Pleasure means that all attempts to separate out some pleasures so as to assign them special worthiness or unworthiness are ultimately misleading. Those who praise “simple pleasures” as more worthy or desirable than “luxurious pleasures” are equally wrong in Epicurean terms. All choices in life are to be evaluated by asking what will be the full consequences of choosing one course or the other. The wise person will evaluate all the consequences - mental, physical, long-term, short-term, and of whatsoever kind - and make choices based on their best estimate of whether in that person’s experience Pleasure or Pain will predominate as a result.

Does this mean that a person considers only the person’s own pleasure and pain? Of course not: Epicurus held that our most important avenue for happy living is our friends, and so the full consequences of our actions take into account how the people around us will respond to our choices, which is a reality that we ourselves must - for very practical reasons - take into account in our calculations.

Epicurus’ atomist views also demanded a more clear view of death. Rather than hopeful equivocation that perhaps the souls of at least great men might survive after death, Epicurus boldly held that because the soul (like everything else) is material (composed of particles and void) then the end of life leads to nothing. In Epicurus’ famous words, death is nothing to us, but not because the fact of death is insignificant.

The fact that human beings die and their consciousnesses come to an end is of critical importance to our estimation of the value of life. Only the living can experience pleasure, and this realization places the importance of living wisely and in good mental and physical health at the center of Epicurus’ worldview. Such is the importance of seeing that death is nothing, and that there is no reward or punishment after death, that the proper view of death as absence of sensation ranks as the second most important in Epicurus’ own list of his key teachings.

While the fact of death is the second most important of Epicurus’ doctrines, there is one doctrine of even greater importance: Epicurus’ claim to hold a valid conception of what it means to be a god. Nothing is more fundamental to the Epicurean worldview that that nothing supernatural - including supernatural gods - can exist. From the very beginning of the philosophy - harking back to the very first step of concluding that “nothing can be created from nothing,” it is foundational to see that the universe as a whole has existed for eternity, and that there is nothing in the complexity that indicates intelligent design or that the universe was created or is supervised by supernatural gods.

But unlike what we know as “atheism” today, Epicurus was emphatic that the Earth is not the only place in the universe where life exists. Epicurus held that there are an infinite number of worlds, some like ours, and some not like ours, on which beings of many types exist.

Epicurus held that there are no supernatural gods directing our lives or rewarding or punishing us after death. Epicurus held that our “spirit” (our mind and intelligence) cannot survive after our death, because our body and all that is within it returns to the particles from which it came. But consistent with his views of the infinite universe, Epicurus held also that if beings outside of earth can find ways to continuously resist the deterioration of their bodies, then they can effectively live on without end.

As part of his total rejection of supernatural religion, Epicurus held that a proper and natural use of the term “god” would be to use that word to designate any and all living beings who are deathless and who succeed in living totally pain-free lives.

Epicurus rejected all aspects of supernatural gods, supernatural souls, and supernatural reward or punishment after death. But Epicurus held that it is not sufficient just to say “no” when people suggest that such gods can and do exist. Epicurus held that the term “gods” should be given real meaning, and that real meaning serves to provide for us a paradigm of how the best life might exist, as totally happy and totally without fear of death.

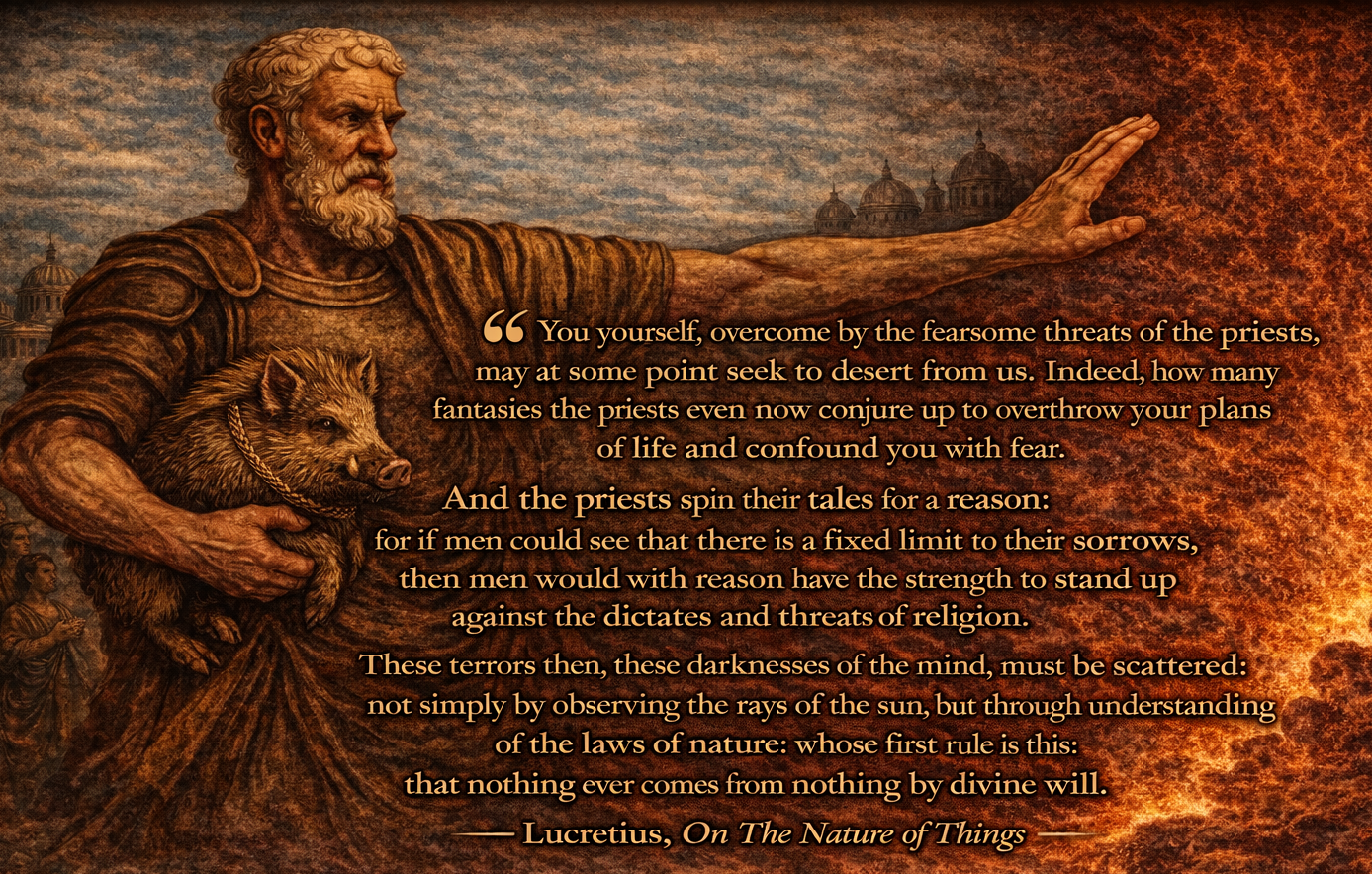

Epicurus spoke of living “as gods among men,” and Epicurus’ poet Lucretius praised Epicurus as someone who should be considered to have been a “god,” if anyone deserved that title. This terminology shocks both militant atheists and militant religionists today, as it did in Epicurus’ own time, but Epicurus was never afraid to shock to the sensibilities of the narrow-minded. The Epicureans insisted that they were not nihilistic atheists, and instead insisted their this view of the nature of gods is the only one worthy of being considered truly divine.

In regard to we humans who cannot duplicate the imperishability of gods, but who wish to do our best to emulate their experience, the Epicureans left to us this formulation, preserved to us by Cicero in his work “On Ends”

The Major Doctrines of Classical Epicurean Philosophy

Section titled “The Major Doctrines of Classical Epicurean Philosophy”Here on our “Welcome” page we can expand on the list of doctrines first listed above as follows, and provide links to other sections of this website and to discussion about each one at EpicureanFriends.com:

Nothing Can Be Created From Nothing

Section titled “Nothing Can Be Created From Nothing”Working solely with the science available two thousand years ago, Epicurus observed that nothing ever arises from nothing, and nothing is ever completely destroyed to nothing. From this Epicurus deduced the existence of atoms - elemental particles moving through empty space from which over time all things are made and return. Given that nothing we observe ever comes into existence except through pre-existing atoms, Epicurus concluded that the universe as a whole has always existed, and that while bodies come and go, there was never a time before the universe as a whole came into being.

Given that the universe has always existed, we can firmly reject the contention that the universe was created at some point in time by supernatural forces. All that we see around us is a result of the natural movement of atoms through void over time. This does not mean that only the atoms are real, however, because Nature tells us that bodies made from atoms are also real . More than anything else, this commitment to the true reality of Nature, and the rejection of all notions of the supernatural, is the starting point for everything else in the Epicurean worldview.

As Epicurus wrote to Herodotus: “Nothing is created out of that which does not exist: for if it were, everything would be created out of everything with no need of seeds.” (Bailey - line 38) This is the way Epicurus teaches us to reason - always stating the evidence behind our conclusions, and never accepting any possibilities based on pure speculation or wishful thinking. The atomic basis of the universe explains how all that we see around us came into existence neither randomly or chaotically, but naturally as a result of elemental particles moving through space. The properties of atoms, and not the dictates of any supernatural forces, determines what can, and what cannot, come into being.

Click here for a slideshow video explaining this doctrine. Find out more in our Physics Forum, our Wiki, and our Discussion Guide. Listen to our special Lucretius Today Podcast Episode 259 dedicated to this topic.

The Universe Is Infinite In Size and Eternal In Time And Has No Gods Over It

Section titled “The Universe Is Infinite In Size and Eternal In Time And Has No Gods Over It”Once Epicurus determined that the universe results from atoms moving naturally through void, he reasoned that the universe could not exist if the atoms were infinite in number but space were limited in size. If that were so, everything would be close-packed and nothing could move. Likewise, the universe could not exist if the atoms were limited in number but space were unlimited in size, If that were so, the atoms would never combine into bodies, any more that debris floating on a vast ocean could ever come together to form solid objects. Epicurus therefore deduced that universe is infinite in size - both the number of atoms and the extent of space are infinite.

From this Epicurus concluded that there can be nothing “outside” the universe as a whole, and so everything that exists is a part of the universe if it exists at all. This conclusion eliminates the possibility of supernatural forces existing “over” or “outside” the universe, and it focuses our attention on the tremendous implications of infinity. Given the infinity of atoms and space, all combinations of atoms which are possible can be expected to come into existence an infinite number of times and places. This does not mean that “anything” is possible, because some combinations of atoms are physically impossible. We know, for example,that there are no “Centaurs,” or “Supernatural Gods,” because it is Nature itself which sets the limits between what is possible and what is impossible.

As Epicurus wrote to Herodotus: “These brief sayings, if all these points are borne in mind, afford a sufficient outline for our understanding of the nature of existing things. Furthermore, there are infinite worlds both like and unlike this world of ours. For the atoms being infinite in number, as was proved already, are borne on far out into space. For those atoms, which are of such nature that a world could be created out of them or made by them, have not been used up either on one world or on a limited number of worlds, nor again on all the worlds which are alike, or on those which are different from these. So that there nowhere exists an obstacle to the infinite number of the worlds.” (Bailey, at 45).

Find out more in our Physics Forum, our Wiki, and our Discussion Guide_ Listen to our special Lucretius Today Podcast Episode 260 dedicated to this topic.

Divinity (The Nature of Gods) Contains Nothing That Is Inconsistent With Incorruption And Blessedness.

Section titled “Divinity (The Nature of Gods) Contains Nothing That Is Inconsistent With Incorruption And Blessedness.”In his characteristic commitment to pursuing truth wherever it leads, Epicurus did not stop at denying the existence of supernatural places or gods. Epicurus observed that we see here on Earth that Nature never makes a single thing of a kind, and that things of a kind are distributed over a spectrum of primitive through advanced conditions. Epicurus therefore reasoned that from this that the universe is filled with other Earths, and other types of living beings, some of which are less advanced and some more advanced than humans. Here on earth we see that life struggles to extend its life and its happiness, and Epicurus deduced that throughout the universe there are beings even more successful at this than humans. We should therefore expect that the universe contains beings which are totally happy and totally deathless, and these beings deserve to be regarded as “gods,” when we consider how that term should be accurately defined.

Even though we do not observe such beings here on earth with our eyes and ears and other senses, our minds are disposed by Nature to realize that such beings are possible. We as humans benefit from identifying these beings as models which we can and do emulate to the extent possible as part of our natural striving to live more happy and healthy lives. Even more importantly, the identification of “gods” having no characteristics inconsistent with blessedness and imperishability enables us to grasp firmly that we have nothing to fear from such beings, as they are exclusively concerned with their own happiness.

As Epicurus said to Menoeceus, “First of all believe that god is a being immortal and blessed, even as the common idea of a god is engraved on men’s minds, and do not assign to him anything alien to his incorruption or ill-suited to his blessedness: but believe about him everything that can uphold his blessedness and incorruption. For gods there are, since the knowledge of them is by clear vision. But they are not such as the many believe them to be: for indeed they do not consistently represent them as they believe them to be. And the impious man is not he who popularly denies the gods of the many, but he who attaches to the gods the beliefs of the many. For the statements of the many about the gods are not conceptions derived from sensation, but false suppositions, according to which the greatest misfortunes befall the wicked and the greatest blessings (the good) by the gift of the gods. For men being accustomed always to their own virtues welcome those like themselves, but regard all that is not of their nature as alien.” (Bailey at 123)

Find out more in our Physics Forum, our Wiki, and our Discussion Guide. Listen to our special Lucretius Today Podcast Episode 256 dedicated to this topic.

Death Is Nothing To Us

Section titled “Death Is Nothing To Us”Given that the universe is entirely natural, contains nothing that is supernatural, we know that no gods have endowed us with immortal souls that can survive death. Epicurus therefore concluded that consciousness is an attribute of the body, and cannot survive outside the body, so our lives end forever at death. This obviously means also that there can be no punishment to fear, or reward to hope for, after death. This knowledge, rather than being cause for despair, frees us to pursue happiness. We are motivated by this, rather than depressed, because the realization that death is nothingness to us means that the reverse is also true: life is everything to us, and we should pursue it with all the vigor we can muster.

The confidence that had no existence for the eternity that passed before we were born, and that we will have no existence for the eternity that will pass after we die, spurs us to focus on making the best use of the time that is available to us. As Epicurus wrote in Principal Doctrine 2, “Death is nothing to us, for that which is dissolved is without sensation; and that which lacks sensation is nothing to us.” Not only does Epicurean doctrine provide motivation to live in the here and now, it gives us strength to face the many painful challenges of life. Epicurus taught that pain is manageable if it continues for very long, and that pain is short if it is intense, but in no case does pain have the power to hold us in its grip indefinitely, because we always have the power to escape pain through death, where no punishment can reach us.

But be clear: life is our most valuable possession, and this is not a sanction for suicide except in the most extreme of circumstances. Epicurus taught that it is a small man indeed who has many reasons for ending his own life. Instead, it is a call to bravery in facing adversity, because as Epicurus wrote to Menoeceus, “There is nothing terrible in life for the man who has truly comprehended that there is nothing terrible in not living.”

Find out more in our Physics Forum, our Wiki, and our Discussion Guide. Listen to our special_ Lucretius Today Podcast Episode 261 dedicated to this topic.

There Is No Necessity To Live Under the Control Of Necessity

Section titled “There Is No Necessity To Live Under the Control Of Necessity”During the brief span of life that is available to us there are no supernatural commandments to follow, and it is necessary for us to act wisely to identify the best life available to us. Therefore Epicurus held that there could be nothing more demoralizing than to think that we have no power over our actions and our future. Epicurus therefore singled out two belief systems as particularly false and harmful. The first falsehood is “Determinism” - the view that due to fate, supernatural forces, or even a purely mechanistic understanding of nature of atoms, we have no control whatsoever over our lives.

Epicurus realized that Determinism is not only damaging, but demonstrably false. Against such mechanistic views of the universe Epicurus advanced not only the physics of “the swerve of the atom,” but he also pointed out the self-contradictory nature Determinism. Epicurus cited this self-contradiction when he wrote: “The man who says that all things come to pass by necessity cannot criticize one who denies that all things come to pass by necessity: for he admits that this too happens of necessity.” (VS 40) And as a practical matter, Epicurus pointed out that we do clearly have control over the supreme choice in life: we have the ability to end our lives at any time, so nothing can compel us to continue to live under necessity.

Epicurus held that if we have the power to make this most important decision in life, we also have the power to control many other lesser aspects of life. Deterministic or fatalistic beliefs are poisons that must be avoided at all costs, so Epicurus wrote “For, indeed, it were better to follow the myths about the gods than to become a slave to the destiny of the natural philosophers: for the former suggests a hope of placating the gods by worship, whereas the latter involves a necessity which knows no placation.”

Find out more in our Physics Forum, our Wiki, and our Discussion Guide. Listen to our special Lucretius Today Podcast Episode 257 and Episode 258 devoted to this topic.

He Who Says “Nothing Can Be Known” Knows Nothing

Section titled “He Who Says “Nothing Can Be Known” Knows Nothing”The second poisonous doctrine that Epicurus identified is known to us today as Radical Skepticism. Skeptics hold that nothing in life can be known with confidence. The Skeptics of Epicurus’ time argued, primarily due to their contention that the senses cannot be trusted, that we can never be certain of anything, and at most some things are “probable.” Even something as obvious as the expectation that if you jump off a canyon wall you will fall to your death is not certain to such philosophers, it is merely “probable.”

Epicurus saw that this confidence-destroying doctrine suffers much the same flaw as Determinism - it is self-contradictory nonsense. Anyone who is ridiculous and absurd enough to advocate that “nothing can be known” is taking you for a fool, because he expecting you to accept that he knows that “nothing can be known.” Epicurus held that that such arguments should not be taken seriously, any more than you should seriously accept the argument from a living person that it would be better never to have been born.

Lucretius spoke for Epicurus in writing: ” Again, if any one thinks that nothing is known, he knows not whether that can be known either, since he admits that he knows nothing. Against him then I will refrain from joining issue, who plants himself with his head in the place of his feet. And yet were I to grant that he knows this too, yet I would ask this one question; since he has never before seen any truth in things, whence does he know what is knowing, and not knowing each in turn, what thing has begotten the concept of the true and the false, what thing has proved that the doubtful differs from the certain? [Book 4:469]

Find out more in our Canonics Forum, our Wiki, and our Discussion Guide. Listen to our special Lucretius Today Podcast Episode 262 devoted to this topic.

All Sensations Are True

Section titled “All Sensations Are True”If Skepticism and Determinism are false, what did Epicurus advocate instead? Epicurus saw that much of the error of conventional thinkers arises from their contention that the faculties given us by nature are incapable of ascertaining truth, and that we have no need of divine revelation or abstract syllogistic logic to determine what is really true. Epicurus vigorously rejected these assertions, and held that the faculties given to us by nature - the five senses, the feelings of pleasure and pain, and the mental anticipatory faculty of prolepsis - are fully sufficient for living in accord with nature.

Epicurus identified that the perceptions of our natural faculties are not at all the same thing as the opinions which we form after processing those perceptions in our minds. Our natural faculties report their perceptions to the mind “truly,” in the sense of “honestly,” without adding any overlay of opinion of their own. Neither the eyes nor the ears nor any other faculty have any memory, and they simply relay to the mind what they perceive at any moment. It is the mind which turns perceptions into opinions. The eyes do not tell our minds what they see and the ears do not tell our minds what they hear, and so on. Truth and error is in the mind’s formation of opinion, not in the faculties given by nature.

The task of determining truth is that of the mind, which requires that we understand both nature and how our faculties process the perceptions provided to us by nature. Our faculties are our only direct contacts with outside reality. As Lucretius wrote as to our “feelings” in general: ” For that body exists is declared by the feeling which all share alike; and unless faith in this feeling be firmly grounded at once and prevail, there will be naught to which we can make appeal about things hidden, so as to prove aught by the reasoning of the mind.” (Book 1:418)

Find out more in our Canonics Forum, our Wiki, and our Discussion Guide. Listen to our special Lucretius Today Podcast Episode 263 devoted to this topic.

Virtue Is Not Absolute Or An End In Itself. All Good And Evil Consists In Sensation.

Section titled “Virtue Is Not Absolute Or An End In Itself. All Good And Evil Consists In Sensation.”Skepticism and Determinism do not exhaust the list of lies and errors plaguing humanity. Epicurus saw that false priests and philosophers have erected a false ideal - “virtue” - as the goal of life. Epicurean philosophy has shocked the sensibilities of conventional thinkers for two thousand years by committing itself boldly to the conclusion that “virtue” is not absolute or an end in itself, and that Nature alone provides us the proper guide of life.

As with “gods,” Epicurus held that “virtue” is a useful concept, but one that has been drastically misunderstood. True “virtue” is not something given by divine revelation, or through logical analysis of ideal forms, but is instead simply a set of tools for living the best life possible. Epicurus held that virtue is not the same for all people, or the same at all times and places, but that instead what is virtuous varies with circumstance, according to whether the action is instrumental for achieving happiness. Good and evil are not absolutes, but instead consist in sensation, as Epicurus explained to Menoeceus: ” “Become accustomed to the belief that death is nothing to us. For all good and evil consists in sensation, but death is deprivation of sensation. And therefore a right understanding that death is nothing to us makes the mortality of life enjoyable, not because it adds to it an infinite span of time, but because it takes away the craving for immortality.” (124)

Likewise, even something as highly regarded as justice is not absolute, but observable only in practical effects: “In its general aspect, justice is the same for all, for it is a kind of mutual advantage in the dealings of men with one another; but with reference to the individual peculiarities of a country, or any other circumstances, the same thing does not turn out to be just for all.” (PD36)

Find out more in our Ethics Forum, our Wiki, and our Discussion Guide). Listen to our special Lucretius Today Podcast Episode 267 devoted to this topic.

Pleasure Is The Guide Of Life

Section titled “Pleasure Is The Guide Of Life”As if Epicurus had not sufficiently shocked conventional sensibilities by dismissing the existence of supernatural gods, and rejecting the pursuit of virtue as an end in itself, Epicurus tripled down on his philosophic revolution by holding that “Pleasure” is not something disreputable, but is indeed the Guide of life. Pointing out that in a universe in which there are no supernatural gods or absolute standards of virtue, it is still necessary to determine how we should live. Epicurus of course looked to Nature, and saw that Nature gives living beings only Pleasure and Pain by which to determine what to choose and what to avoid

Flagrantly disregarding the wrath of the orthodox, Epicurus proclaimed Nature quite literally gave humanity “nothing” but Pleasure and Pain as guides. While there are many shades of feeling, all of them resolve down to being categorized pleasurable or painful, and there are no in-between, mixed, or third alternatives. As Epicurus’ biographer summarized, “The internal sensations they say are two, pleasure and pain, which occur to every living creature, and the one is akin to nature and the other alien: by means of these two choice and avoidance are determined.“ (Diogenes Laertius 10:34)

Epicurus did not consider this to be wordplay or wishful thinking, but the foundation on which to erect the highest and best way of life. Epicurean philosophy always looks to Nature rather than to wishful thinking, and so the Epicureans taught: “Moreover, seeing that if you deprive a man of his senses there is nothing left to him, it is inevitable that Nature herself should be the arbiter of what is in accord with or opposed to nature. Now what facts does she grasp or with what facts is her decision to seek or avoid any particular thing concerned, unless the facts of pleasure and pain? (Torquatus in Cicero’s On Ends 1:30)

Find out more in our Ethics Forum, our Wiki, and our Discussion Guide). Listen to our special Lucretius Today Podcast Episode 268 devoted to this topic.

By Pleasure We Mean All Experience That Is Not Painful (The Absence of Pain)

Section titled “By Pleasure We Mean All Experience That Is Not Painful (The Absence of Pain)”One might think that stirring philosophers, priests, and politicians to exasperation on the topics of “Gods,” and “Virtue” would be enough of a revolution for any one philosopher. But Epicurus’s commitment to the truth led him to drive forward to correct the erroneous view of “Pleasure” as well. While virtually everyone before him had properly understood “pleasure” as including sensory stimulation, Epicurus saw this definition as perversely narrow. Epicurus therefore turned to clarifying how the term “pleasure” properly applies to more than sensory stimulation, just as the term “gods” properly applies only to non-supernatural beings.

Epicurus realized that since Nature has given us only two feelings, if we are alive and feeling anything at all we then are feeling one or the other of the two. That means if we are not feeling pain, what we are feeling is in fact pleasure. This means that “Pleasure” involves much more than the sensory stimulation, which we have been trained by priests and virtue-based philosophers to consider the only meaning of the term. Once we understand that all experiences in life that are not painful are rightly considered to be pleasurable, Epicurus taught us that we can then use the term “Absence of Pain” as conveying exactly the same meaning as “Pleasure.” The benefit of this perspective is that Pleasure be comes something that is widely available through a myriad of ways of life that do not require great pain to experience. Pleasure becomes a workable term to describe the goal of life, and a life of continuous pleasure in which pleasures predominate over pain becomes possible for all but the very few who face extreme circumstances (and even they need not face more pain than pleasure indefinitely.)

Just as we should understand “gods” to refer to living beings who are blessed and imperishable, and “virtue” to refer to actions which lead to happiness, we should understand “pleasure” to refer to all experiences of life that are not painful. Torquatus preserves for us this explanation: “Therefore Epicurus refused to allow that there is any middle term between pain and pleasure; what was thought by some to be a middle term, the absence of all pain, was not only itself pleasure, but the highest pleasure possible. Surely any one who is conscious of his own condition must needs be either in a state of pleasure or in a state of pain. Epicurus thinks that the highest degree of pleasure is defined by the removal of all pain, so that pleasure may afterwards exhibit diversities and differences but is incapable of increase or extension.“ (On Ends 1:38)

Find out more in our page dedicated to The Epicurean View of Pleasure, our Ethics Forum, our Wiki, and our Discussion Guide). Listen to our Special Lucretius Today Podcast Episode 269 devoted to this topic.

Life Is Desirable, But Unlimited Time Contains No Greater Pleasure Than Limited Time

Section titled “Life Is Desirable, But Unlimited Time Contains No Greater Pleasure Than Limited Time”As we close this list of some of Epicurus’s most important doctrines, by now it should be no surprise that Epicurus held that life is very desirable. How could he reason otherwise, given that life is a necessity for the experience of pleasure, and pleasure is what Nature has given us as the goal to pursue? But Epicurus knew that humanity is not only fearful of death, but that we covet so strongly the possibility of living forever that we are constantly tempted by mystical claims offering us false promises of eternal life. Epicurus saw that he needed to answer that challenge, and deal with the concern that the inevitable death of our friends and ourselves constitutes a stain on life which forever spoils our happiness. Such a negative view of life was unacceptable to Epicurus, and he pointed out that death in fact does not deprive us of nearly so much as we think it does.

Epicurus explains to us that his philosophy allows us to see that no matter how long we live, unlimited time can contain no “greater” pleasure than limited time. This is because time (duration) is only one aspect of pleasure. It makes no more sense for us to seek the longest time of life as the greatest pleasure as it would for us to measure the largest quantity of food at a banquet as being the best way to eat. While time is a relevant dimension, time is not at all the complete picture of pleasure, because pleasure involves not just time but intensity, and the part of the our experience that is affected; and in the end the “best” pleasure is a subjective assessment. Epicurus tells us we can see this by considering the person at a banquet, as already mentioned. Epicurus wrote to Menoeceus that the wise man at a banquet will choose not the most food, but the best food, and held that our desire should not be for the longest life, but the most pleasant life.

When you remember the Epicurean worldview that there is no supernatural god, no absolute virtue or right and wrong to which we must conform, we can see that the decision as to what is the best life - the most complete life for us - is a matter for us to decide, and that time is neither the most important factor nor the determiner of our decision. Epicurus teaches us to compare our lives to a banquet, or to a jar that we are filling with water. What we should want to do is not to eat the most food, or continue pouring water into the jar after it is full, but to see that the “fullness of pleasure” and the completeness of life is something that we can retain despite our limited lifespans. No jar can be filled more full than full, and no life can be made more complete than complete: once we see that our target is a “complete” life, then “variation” - or the continuous adding-on of new pleasurable experiences — does not make the experience any more pleasant. And since it is pleasure that Nature gives us as our goal, Epicurean philosophy gives us a fighting chance - if we work to understand it and apply it properly - to consider our lives to be complete and in no need of unlimited time.

Find out more in our Ethics Forum, our Wiki, and our Discussion Guide). Listen to our special Lucretius Today Podcast Episode 270 devoted to this topic.

The Sections Of This Website

Section titled “The Sections Of This Website”EpicurusToday.com is divided into the following sections:

Blog - Here you will find blog posts covering various aspects of Epicurean philosophy, organized by title, tag, author, and date.

Lucretius Today Podcast - Here you will find episodes of the Lucretius Today Podcast exploring Epicurean philosophy through the lens of Lucretius’ De Rerum Natura.

Key Concepts - Here you will find detailed explanations of fundamental Epicurean philosophical concepts.

Core Primary Sources - Here you will find a curated collection of key Epicurean texts, including ancient sources, translations, and modern commentaries.

Other Resources - Here you will find a curated collection of key Epicurean texts, including ancient sources, translations, and modern commentaries.

The EpicureanFriends Forum - Here you will find discussions and resources from the EpicureanFriends community.

Zoom Meetings - Here you will find notes and summaries from regular Zoom discussion meetings about Epicurean philosophy.

Site Map - Here you will find a comprehensive overview of all content available on this site.

Quick Reference To Primary Sources

Section titled “Quick Reference To Primary Sources”- The Letters and Doctrines of Epicurus With Commentary by Diogenes Laertius

- Lucretius “On The Nature of Things”

- Cicero’s Torquatus on Ethics

- Cicero’s Velleius on The Nature of The Gods

- Topical Outline of Major Epicurean Quotations